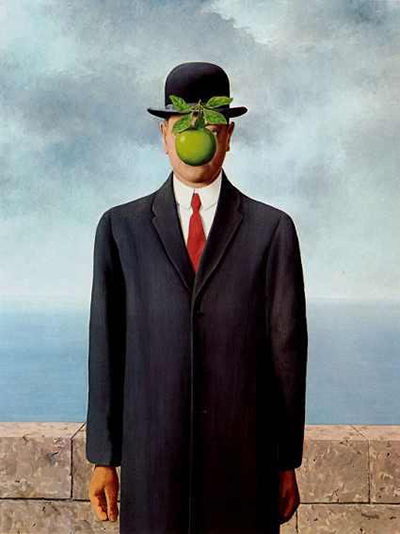

When thinking of Surrealism, the first thing that comes to mind is often the image of Dalí’s melting clocks and Magritte’s pipes. While these famous surrealist paintings are key aspects of the art style, Surrealism is much more than distorted imagery and play with words. The famous artists who came together after the First World War under the name of Surrealism were considered as a group of senseless people by many art critics and among the public at that time. Yet they were quite serious about their movement and ended up changing art history worldwide. As the longest-running avant-garde movement of the 20th century, its scope is unparalleled regarding the influence it exerted on modern art and culture.

What’s in a Word

The term “surrealist” meaning “beyond reality” was coined by the French avant-garde poet Guillaume Apollinaire in 1917 describing Jean Cocteau’s ballet “Parade” and his own play “The Mammaries of Tiresias”. French theoretician and writer André Breton, who is widely considered the founder of Surrealism, reinterpreted the term in homage to the poet, who had died one year after. In contrast to Apollinaire, Breton coined “Surrealism” in terms of Sigmund Freud’s unconscious mind. Breton was a former medical student and had served as a psychiatric orderly during the First World War. After participating in the Dada art movement, he became determined to probe the secret recesses of the mind working as a poet, wondering what aesthetic discoveries might come to light.

The Movement in Language and the Arts

Like Dada, Surrealism strove to revolutionize language and renew its primary function, no longer regarding words as passive objects but as autonomous entities. It rejected rational ways of thinking about the world, aiming to revolutionise and poetise the human experience by asserting the value of the unconscious mind. The movement included proponents from literary, philosophical, and artistic circles, looking for the magic and strange beauty in the uncanny and unconventional.

First Manifesto

Breton drafted the “Surrealist Manifesto” in 1924, defining the movement as:

“Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express—verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner—the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.”

The manifesto further highlighted the importance of the dream as a reservoir of inspiration and the apprehension of Surrealism as the juxtaposition of two distant realities united to create a new one. Accordingly, many surrealist artists used automatic writing, drawing, or painting to unlock their ideas and images from the unconscious, while others sought to depict dreamlike scenes.

Psychoanalysis and Karl Marx

Throughout the 1930s, Surrealism became a diverse international movement. The rejection of conventional and moral values deeply affected writers, artists, photographers, and filmmakers around the world. Besides the group led by André Breton, another Surrealist faction grouped around George Bataille.

Disdaining literary realism and rationalism, many famous Surrealist artists believed that the rational mind suppressed the power of the imagination. Besides psychoanalysis, a further impactful influence was exerted by the theories of Karl Marx. The Surrealists hoped that the psyche would have the power to expose the contradictions in everyday life and to incite revolution. Breton conceived of Surrealism as a revolution of the mind, which would fundamentally metamorphose experiences in everyday life. Surrealism was not as much interested in the irrational for its own sake, but much more in merging the contradictory states of dream and reality into a more compelling form of life, which Breton understood as a kind of surrealist consciousness.

Psychoanalysis and Freud’s theories of the mind provided Surrealist artists with a way to move beyond a superficial apprehension of the world. However, while Freud was interested in how daily life left impressions in dreams, the Surrealists experimented with the ways in which our dream world could be expressed in everyday experiences, in art and writing.

Diversity of the Movement

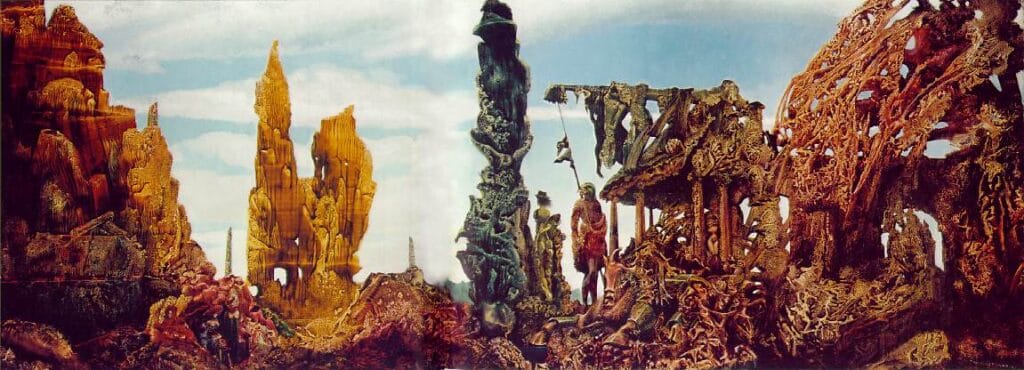

Famous surrealist paintings such as René Magritte’s visual illusions and Salvador Dalí’s melting clocks have become familiar images of the movement. Yet Surrealist artworks were incredibly diverse. For example, Max Ernst experimented with techniques such as frottage, as well as with decalcomania, a technique in which he transferred paint from one surface to another, to reveal forms in fantastic landscapes and hidden textures. Artist like Spanish Surrealist Dalí with his “Lobster Telephone” and German-Swiss artists Meret Oppenheim with her “Object” – a fur-covered tea-cup and spoon, aimed at de-familiarising everyday experiences. Man Ray exemplified with his surrealism photography the reconciliation of dream and reality, of art and life. He revealed a new awareness of the everyday world with the incorporation of reflections, distortions, shadows, montage, and collage, working both across avant-garde and commercial domains.

While famous surrealist painters Magritte, Ernst, and Dalí showed more composed, dreamlike, and otherworldly compositions, another direction of the movement was exemplified by artists such as Joan Miró and André Masson, who emphasized the automatist element. Yet all were committed to what can be called “poesie peinture” – a visionary, poetic form of painting.

The Second Manifesto

By the 1930s, the surrealist movement was divided between those who wanted to promote communism with their art, and those leaning towards the principle of art for art’s sake. Breton tried to combine both ways by sympathizing with communism but believing art served a purpose as a means in itself. In his second manifesto of Surrealism, Breton stressed the goal of liberating the individual through self-expression. Yet he criticised the use of automatism and dreamscapes if they ended only in art with no further purpose.

The Second World War and Movement Overseas

As an interwar movement beginning in Paris in the 1920s, Surrealism responded to a post First World War period and witnessed the rise of fascism across Europe. With the beginning of the Second World War, most major proponents of Surrealism had been forced to flee Europe in fear of Nazi persecution. Max Ernst’s “Europe After the Rain II” reflects this post-apocalyptic setting at the height of the Second World War, suggesting eroded landscapes, bombed-out buildings, dead human and animal corpses.

The surrealist artists emigrating to various countries for refuge spread the movement across the Atlantic, where it took root in the Americas. Most surrealists relocated to New York, where they had a strong impact on the emerging avant-garde. However, the responses towards surrealism varied strongly: some adapted the techniques without interest in the unconscious or Communism; others took the unconscious as well as the techniques as starting point to develop new paths, for example the Abstract Expressionism.

Artists such as Walter Quirt, O. Louis Guglielmi, Peter Blume, and Ivan Albright can be considered as American surrealists. Unlike their European counterparts, the imagery of these artists remained more distant to dreamlike pictures, but they still used a surreal fashion to address social issues. Some of the “social surrealists”, such as Guglielmi and Quirt, eventually turned to a more psychological form of the movement. A number of female surrealists such as Leonora Carrington, Kay Sage, and Dorothea Tanning fell into a category of their own, since they could neither be categorized as proponents of magical realism of the Americans nor the hallucinatory surrealism of the Europeans. The movement further inspired an entire generation of American painters to come, such as Jackson Pollock and in Latin America Frida Kahlo.

Movement in the 21st Century

While many argue that surrealism as an identifiable movement ended with the death of the founder of surrealism André Breton in 1966, others emphasize that its impact on the arts remains relevant and vital until today. Not only did Surrealism influence an entire generation of post-structuralist theorists like Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Lacan; it also led to a disruption of the hierarchical relationship between high and popular culture, to a transformation of everyday life, leaving an imprint on academic disciplines like cultural studies, and making possible a new kind of intellectual thinking.

You might also enjoy reading the following posts by Pigment Pool:

Joan Miró: Surrealism Through the Eyes of an Abstract Genius

Famous Impressionist Paintings: Why You Need One in Your Home