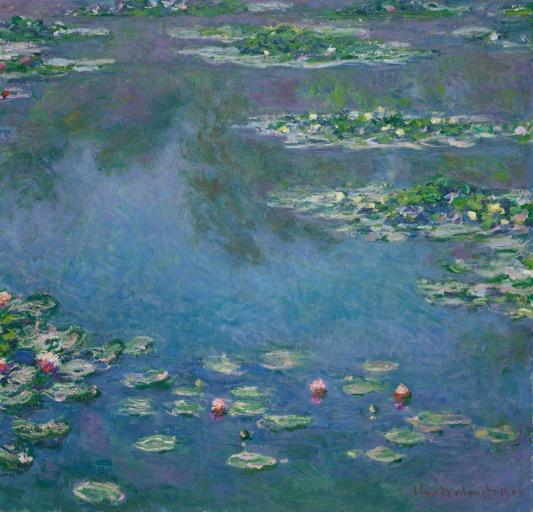

Have you ever left a museum after seeing a Vincent van Gogh or Claude Monet paintingPainting is a fundamental form of visual art that has been practiced for thousands of years. It involves applying pigment to a surface such as canvas, paper, or a wall. Painting can be explored through various styles, techniques, and mediums, each offering unique possibilities for expression and creativity. Historical Background • Ancient Beginnings: The history of painting dates back to More and felt your mood instantly lift? Or perhaps you hung up a new Egon Schiele print at home, and suddenly the room feels more inviting?

Even the simple act of doodling on a scrap of paper while on the phone might bring a surprising sense of satisfaction.

These moments hint at the growing field of art psychology and neuroaesthetics, which reveal how positive emotional responses triggered by art can directly improve mood and, in turn, support overall health and well-being.

The Framework

The scientific study of aesthetics, particularly within the fields of neuroaesthetics and art psychology, focuses on one primary question: What is an aesthetic experience, and how can we scientifically understand it?

At the heart of this emerging discipline is the desire to break down the components of art appreciation and investigate how our sensory and motor systems, emotions, and cognition come together to form what we call an aesthetic experience.

Understanding the Components of Aesthetic Experience

Neuroaesthetics looks at how we perceive and process art through the lens of cognitive science. The human brain interacts with art by engaging various sensory and motor systems—such as how our eyes track the colors, lines, and shapes of a paintingPainting is a fundamental form of visual art that has been practiced for thousands of years. It involves applying pigment to a surface such as canvas, paper, or a wall. Painting can be explored through various styles, techniques, and mediums, each offering unique possibilities for expression and creativity. Historical Background • Ancient Beginnings: The history of painting dates back to More.

But the sensory aspect alone doesn’t fully explain why we might find a work of art beautiful, moving, or thought-provoking. The experience of art also involves our emotional and reward systems, which help us interpret and valueIn color theory, value refers to the lightness or darkness of a color. This concept is crucial for artists and designers because it helps create depth, contrast, and visual interest in their work. Value is one of the three properties of color, alongside hue and saturation. Defining Value Value indicates how light or dark a color appears. It ranges from More what we see.

For instance, consider the difference in emotional response when viewing a serene landscape versus a chaotic abstract piece. Your brain processes the visual details, but the emotional evaluation is what makes the experience unique to you.

Factors like personal preference, cultural background, and emotional resonance influence how you react to art. This is where the emotion-valuation aspect comes into play, helping to translate sensory input into feelings of pleasure, excitement, or discomfort. But what role does knowledge or prior experience play in shaping this response?

The Influence of Knowledge and Meaning

Knowledge and context often play a vital role in how we experience art. Is art appreciation purely sensory and emotional, or does deeper meaning contribute to our overall experience? Research suggests that people with a background in art or familiarity with certain styles and movements tend to engage more deeply.

For example, a viewer familiar with the Cubist works of Pablo PicassoPablo Picasso (1881–1973), was a Spanish painter, sculptor, graphic artist, and resident in France from 1904. He was a dominant figure in avant-garde movements in the first half of the 20th century due to his technical versatility and prolific inventiveness. picasso-self-portrait Picasso’s progression in his early work is largely categorized by predominant colour schemes: His Blue Period (1901-1904) features motifs More might appreciate the innovative challenge to traditional forms, whereas someone new to CubismSynthetic cubism was the later period of the Cubist art movement generally dated from 1912 – 1919. Artists of Synthetic Cubism moved away from the multi-perspective approach of Analytical Cubism in favour of flattened images that dispensed allusions of the three-dimensional space. Pablo Picasso, Clarinet, Bottle of Bass, Newspaper, Ace of Clubs (2013) The approach of the analytical phase was More might focus solely on the visual impact. Both experiences are valid, but additional knowledge can elevate the emotional and cognitive experience of art.

Sensory and Motor Systems: How Our Brains Respond to Art

At the core of our engagement with art are the sensory and motor systems, which allow us to perceive and respond to what we observe. The brain’s mirror neuron system sometimes mimics the physical actions involved in creating art, even when we are merely observing it.

This phenomenon enhances our connection to the process of art-making. When we see a detailed brushstroke, for instance, our brain may simulate the motion involved, adding another layer to our appreciation. It’s why watching someone paint or sculpt can be as engaging as viewing the final piece.

Art to Improve Health

Numerous empirical studies in the field of art psychology since the beginning of the 21st century suggest that aesthetic experiences related to art – all forms such as paintingPainting is a fundamental form of visual art that has been practiced for thousands of years. It involves applying pigment to a surface such as canvas, paper, or a wall. Painting can be explored through various styles, techniques, and mediums, each offering unique possibilities for expression and creativity. Historical Background • Ancient Beginnings: The history of painting dates back to More, music, and theatre included – can improve a person’s health (see sources below). However, how aesthetic appreciation and interaction directly affects our emotional as well as cognitive states to promote both the health of mind and body is still not universally proven. Yet many studies indicate, that exposing oneself to art may significantly change our mood and reduce stress levels. Studies conducted in people visiting museums and art galleries – both with figurative and abstract art Abstract artworks diverge from depicting recognizable scenes or objects and instead use colors, forms, and lines to create compositions that exist independently of visual references from the natural world. This movement, which gained momentum in the early 20th century, was propelled by artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimir Malevich. These artists aimed to explore spiritual, emotional, and More – showed that the memory among those people improved significantly, that stress levels decreased, and social inclusion ameliorated.

Abstract artworks diverge from depicting recognizable scenes or objects and instead use colors, forms, and lines to create compositions that exist independently of visual references from the natural world. This movement, which gained momentum in the early 20th century, was propelled by artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimir Malevich. These artists aimed to explore spiritual, emotional, and More – showed that the memory among those people improved significantly, that stress levels decreased, and social inclusion ameliorated.

A study with people with dementia who visited art galleries showed, that the individual well-being was promoted, social interaction improved, and cognitive enhancement was achieved. Using art therapy among groups of vulnerable people, among them adolescents, elderly, and people with mental disorders, proved to be an effective therapeutic tool to promote psychological and physical well-being.

Art to Improve Health

Since the early 21st century, a growing body of research in art psychology has suggested that engaging with art—whether it’s paintingPainting is a fundamental form of visual art that has been practiced for thousands of years. It involves applying pigment to a surface such as canvas, paper, or a wall. Painting can be explored through various styles, techniques, and mediums, each offering unique possibilities for expression and creativity. Historical Background • Ancient Beginnings: The history of painting dates back to More, music, theatre, or other forms—can positively impact our health.

Though the precise mechanisms behind how aesthetic experiences influence both mental and physical well-being are not fully understood, evidence increasingly shows that exposure to art can improve mood, reduce stress, and enhance cognitive function.

The Impact of Art on Emotional and Cognitive States

One study focused on people visiting museums and art galleries found that those who interacted with both figurative and abstract art Abstract artworks diverge from depicting recognizable scenes or objects and instead use colors, forms, and lines to create compositions that exist independently of visual references from the natural world. This movement, which gained momentum in the early 20th century, was propelled by artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimir Malevich. These artists aimed to explore spiritual, emotional, and More experienced significant improvements in memory retention, reduced stress levels, and greater social inclusion.

Abstract artworks diverge from depicting recognizable scenes or objects and instead use colors, forms, and lines to create compositions that exist independently of visual references from the natural world. This movement, which gained momentum in the early 20th century, was propelled by artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimir Malevich. These artists aimed to explore spiritual, emotional, and More experienced significant improvements in memory retention, reduced stress levels, and greater social inclusion.

Art doesn’t just stimulate the senses—it has the power to reshape how we think and feel on a deeper level. For individuals dealing with high stress or cognitive decline, regular exposure to art has been shown to provide relief and even cognitive stimulation.

Art Therapy: A Growing Field

Art therapy has emerged as a powerful tool for improving mental health, especially among vulnerable populations like adolescents, the elderly, and individuals with mental health disorders.

Engaging with art in a therapeutic setting offers a creative outlet for emotional expression and helps people process trauma, anxiety, or depression without relying solely on verbal communication. Studies show that art therapy promotes psychological and physical well-being by helping people manage emotions and develop coping skills.

In therapeutic settings, patients often report a sense of relief and clarity after creating or engaging with art.

Whether through paintingPainting is a fundamental form of visual art that has been practiced for thousands of years. It involves applying pigment to a surface such as canvas, paper, or a wall. Painting can be explored through various styles, techniques, and mediums, each offering unique possibilities for expression and creativity. Historical Background • Ancient Beginnings: The history of painting dates back to More, sculptingSculpting is a captivating art form that involves shaping materials into three-dimensional forms. This practice has a rich history and includes various techniques and materials, each offering possibilities for artistic expression. Historical Background • Ancient Origins: Sculpting traces back to prehistoric times with early examples like the Venus of Willendorf, a small figurine carved from limestone. These early works often More, or even discussing a piece of artwork, the process taps into the brain’s emotional and reward systems, fostering emotional resilience and a sense of accomplishment.

Art to Enhance Learning and Boost Dopamine

In recent years, art-based pedagogy—incorporating visual art, theatre, paintingPainting is a fundamental form of visual art that has been practiced for thousands of years. It involves applying pigment to a surface such as canvas, paper, or a wall. Painting can be explored through various styles, techniques, and mediums, each offering unique possibilities for expression and creativity. Historical Background • Ancient Beginnings: The history of painting dates back to More, and music into education—has shown great potential for enhancing learning, particularly in healthcare and therapeutic settings.

Studies show that students who engage with art develop important skills beyond academic knowledge. These include empathy, nonverbal communication, and observational skills, all of which are critical in fields like healthcare.

Enhancing Learning through Art

Art-based learning helps activate brain areas associated with creativity, critical thinking, and emotional processing. By using art as a teaching tool, students improve their ability to understand complex emotional concepts and engage with material in a more immersive way.

For example, healthcare students participating in role-playing exercises or visual art projects often show improved empathy and interpersonal skills—key abilities for patient care.

The Science Behind Dopamine and Art

On a biological level, engaging with art stimulates the release of dopamine, the neurotransmitter responsible for feelings of reward and pleasure. This response isn’t limited to observing art—it happens during the creative process as well. Whether creating a paintingPainting is a fundamental form of visual art that has been practiced for thousands of years. It involves applying pigment to a surface such as canvas, paper, or a wall. Painting can be explored through various styles, techniques, and mediums, each offering unique possibilities for expression and creativity. Historical Background • Ancient Beginnings: The history of painting dates back to More, playing music, or engaging in art therapy, the act of completing an artwork often brings a sense of joy and satisfaction due to the dopamine release.

Art therapy builds on this concept, especially in mental health care. Research shows that art therapy sessions can help reduce anxiety, improve mood, and encourage positive social interactions. The release of dopamine and other “feel-good” chemicals like endorphins and oxytocin contribute to the emotional benefits of art-based activities.

Negative Art for Positive Feelings

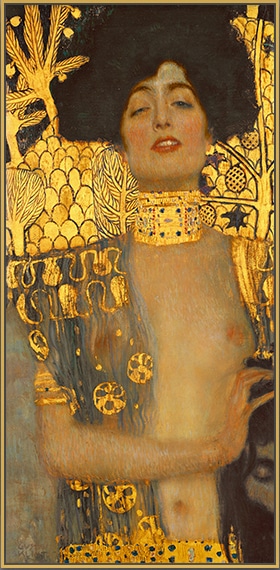

And finally, neuroimaging studies highlighted those direct emotional responses to artwork are associated with recruitment of brain circuitry involved in pleasure, reward, and the regulation of emotion. Further experiments in the field of art psychology and neuroaesthetics show that people report being strongly engaged by art with content that could be considered negative.

The experience of feeling moved would then combine the negative affect with an equal level of positive affect. This implies that we can allow ourselves to be moved by tragedy in art because it is distant from us, clearly considering it as a fictional world of virtual reality. The horror of Edvard Munch’s scream, the black colour fields by Mark Rothko which have been read as suicide notes, and the terrifying scene of Judith with the decapitated head of Holofernes in Gustav Klimt’s masterpiece, all could give us a feeling of enlightenment. The experience of being moved by such works is not only pleasurable but can also be highly meaningful since we reflect on the nature of our feelings.

What Still Needs to be Done

Despite the significant strides made in understanding the relationship between art, aesthetics, and the brain, many questions remain unanswered. Neuroaesthetics and the psychology of art are still emerging fields, and much of their potential is yet to be uncovered.

For instance, does viewing a masterpiece like Van Gogh’s Starry Night produce the same effects as watching a powerful stage drama? How do these experiences differ in their ability to shape behavior or enhance our capacity for empathy?

Research has already established that aesthetic experiences can benefit mental and physical well-being, but the specific mechanisms through which art influences empathy and social behavior remain less clear.

Can regular engagement with art cultivate long-term changes in how we relate to others? Could certain forms of art be more effective in fostering emotional intelligence or reducing societal divisions? These are just some of the questions calling for deeper exploration.

Additionally, most research focuses on the immediate emotional and physiological effects of art. A greater understanding of how sustained engagement with art—whether through regular museum visits, art therapy, or simply appreciating beauty in daily life—could offer valuable insights into the long-term impact of art on the human experience.

As we continue to uncover how the brain responds to art, further research will help answer these pressing questions and broaden our understanding of how art shapes human behavior and well-being.

FAQs

- What is neuroaesthetics? Neuroaesthetics is a branch of neuroscience that studies how the brain responds to art and aesthetic experiences. It explores how we perceive and process beauty, art, and other forms of sensory stimulation and how these experiences affect emotions, cognition, and well-being.

- How does art improve mental health? Engaging with art, whether by viewing or creating it, can reduce stress, improve mood, and enhance cognitive function. Art therapy, in particular, is used to help people process difficult emotions, manage anxiety, and promote overall psychological well-being.

- Can art really reduce stress? Yes, numerous studies show that exposure to art—whether by visiting a museum or engaging in creative activities—can lower cortisol levels (the hormone associated with stress), leading to a more relaxed mental state.

- What is the role of dopamine in art appreciation? Dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and reward, is released in the brain when we engage with or create art. This dopamine release enhances feelings of satisfaction and joy, making art a powerful tool for boosting emotional well-being.

- Is art therapy effective for people with mental health disorders? Yes, art therapy has proven to be an effective treatment for a range of mental health issues, including anxiety, depression, and trauma. It provides a creative and non-verbal outlet for individuals to express their emotions and gain clarity in processing their experiences.

- How does art help improve learning in educational settings? Integrating art into education, especially in fields like healthcare, enhances critical skills such as empathy, nonverbal communication, and emotional understanding. Art-based learning engages different parts of the brain, improving creativity and problem-solving abilities.

- Does it matter if I understand art to benefit from it? While deeper knowledge of art history or styles can enhance the aesthetic experience, you don’t need to fully understand a piece of art to enjoy its emotional or psychological benefits. The experience can be both personal and universal, depending on your perspective.

- Can art influence empathy? Yes, engaging with certain forms of art, particularly those that depict human emotions or narratives, can increase empathy. By connecting with characters or scenes in art, people often gain a deeper understanding of others’ experiences and emotions.

- Is there a difference between visual art and performance art in terms of brain impact? Both visual art and performance art can stimulate emotional and cognitive responses, but they might activate different brain regions. Performance art often involves more dynamic social and emotional engagement, while visual art focuses on sensory perception and emotional evaluation.

- What are the long-term benefits of engaging with art? While much research focuses on the immediate benefits of art, sustained engagement with art through regular museum visits, creative activities, or art therapy can have long-term effects on emotional resilience, cognitive function, and social well-being.

Recommended Reading:

You might also enjoy reading the following posts by Pigment Pool

Facts to Know about Surrealism: Changing the Course of Art History

The Psychology of Colour in Art: Masterpieces and Mind Games