- Gustave Courbet – Burial at Ornans (1849—1850)

- Claude Monet – Impression Sunrise (1873)

- Paul Cézanne – Mont Sainte-Victoire (1904—1906)

- Pablo Picasso – Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907)

- Hilma af Klint – Evolution, No 15, Group IV, The Seven-pointed Stars (1908)

- Henri Matisse – The Dance (1909-1910)

- Georges Braque – Man with a Guitar (1911-1912)

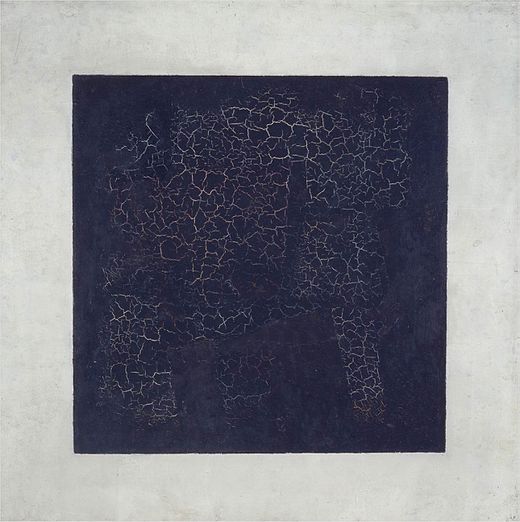

- Kazimir Malevich – Black Square (1915)

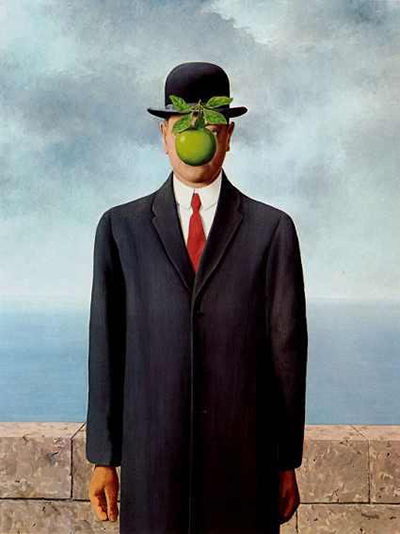

- Réne Magritte – The Son of Man (1946)

- Jackson Pollock – Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) (1950)

The modernist art period began in the middle of the 19th century with the dawn of the industrial revolution in Western Europe. The pace of life changed dramatically with the invention of technologies such as machine-powered factories, the internal combustion engine, and electrical power generation in urban areas. The urban metropolises expanded with many people migrating from the rural farms to city centres to find work. Artists were drawn to these new visual landscapes bustling with modern fashions and spectacles, creating some of the most famous paintings known today.

The advent of photography was one more major technological development, which seemed to make painting obsolete, since it could reproduce any scene with perfect accuracy. The photograph posed a serious threat to the classical modes of representing objects, since painting could not capture the same degree of detail. Artists were drawn to find new modes of expression, representing their experience of the newness of modern life in innovative ways, which lead to new paradigms in art and to some of the most influential paintings. Works of art became more personal, having artists reinventing their work in the terms of the impressionist, expressionist, abstract, minimalistic, or deconstructed.

Even though modern art as a term applies to a large number of artistic genres spanning more than one century, the era is characterized by the intent to portray their subjects as it exists in the world aesthetically, according to the artist’s personal perspective. It is exemplified by the rejection of traditional styles and values, which is especially eminent in the following ten seminal, world-famous paintings of modern art.

Gustave Courbet – Burial at Ornans (1849—1850)

The first modern artist to stand on his own, establishing himself as independent thinker and venturing beyond what constituted acceptable forms of traditional art endorsed by state-run academies, was Gustave Courbet. With his influential painting “Burial at Ornans”, in which he portrayed the funeral of a common peasant man, he scandalized the French art world. It treats an ordinary provincial funeral with unflattering realism in a giant scale, which was traditionally reserved for the religious or heroic scenes of the history painting genre.

When Courbet exhibited his painting at the 1850 Paris Salon, it evoked an explosive reaction and brought Courbet instant fame. The Academy and art critics denunciated the depiction of dirty farm workers around an open grave, devoid of sentimental rhetoric that was expected in genre work. Critics accused Courbet of the deliberate pursuit of ugliness. Eventually, the public grew more interested in the artist’s realist approach and the decadent, lavish fantasy of Romanticism lost popularity.

Claude Monet – Impression Sunrise (1873)

In his seminal painting “Impression, Sunrise” Monet focused on light and atmosphere within the landscape scene depicting the port of Le Havre, his hometown in the Northwest of France. It gives a suggestion of the early morning mist clogged with industrial smoke of the city. Monet stripped away the details to a bare minimum: the dockyards in the background are merely suggested by a few brushstrokes, as are the dark vessels which contrast against the hazy background, interspersed with orange and yellow hues of the red sun. Little detail is only visible for some smaller boats in the foreground, seemingly being propelled by the water currents.

The colours are restrained, and the paint applied in very thin washes, at places even leaving the canvas visible, making the painting appear strongly atmospheric. It represents Monet’s swift attempt to capture a fleeting moment which became characteristic for the Impressionism movement. The near abstract technique compels almost more attention than the subject matter itself in this world famous painting.

Paul Cézanne – Mont Sainte-Victoire (1904—1906)

After first joining the Impressionism art movement, Paul Cézanne soon lost interest in reproducing momentary observations and began to focus on a more formal, constructivist approach. In his influential painting “Mont Sainte-Victoire”, he simplified and concentrated colours, standardized his brushstrokes so as to turn them into units, relying more upon the use of geometric motifs.

Cézanne stated himself, that nature was best depicted in terms of three-dimensional geometric shapes, such as the cone, triangles, the sphere, and the cylinder. In his attempt to create a more intellectual style of painting, he often returned to the same subject such as the Mont Sainte-Victoire. His rough and daring form of modern art, which is widely classified as belonging to Post-Impressionism, was largely incomprehensible to the general public, but highly influential on other modernists, especially Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

Pablo Picasso – Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907)

In his world-famous painting “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon”, Picasso did away with pre-existing artistic conventions, such as naturalism and perspective, and laid the foundations of Cubism. He created hundreds of preparatory paintings and drawings over a period of six months, reflecting Paul Cézanne’s structured depiction of objects and his prismatic arrangement of space.

The painting further reflected his fascination with African, Oceanic, and Iberian masks, as well as his own complex relationship with women. The title, which translates to “The Young Women of Avignon” refers to Avignon Street in Barcelona, home to the prostitutes the artist frequented. The five women with their pinkish-peach-coloured bodies appear larger than human scale, filling the space of the influential painting. Their shoulders, limbs, hips are depicted with angular lines and flat, geometric planes. Cubic shapes and half-circles form their breasts. Their faces, too, are radically simplified and appear to be modelled after African masks.

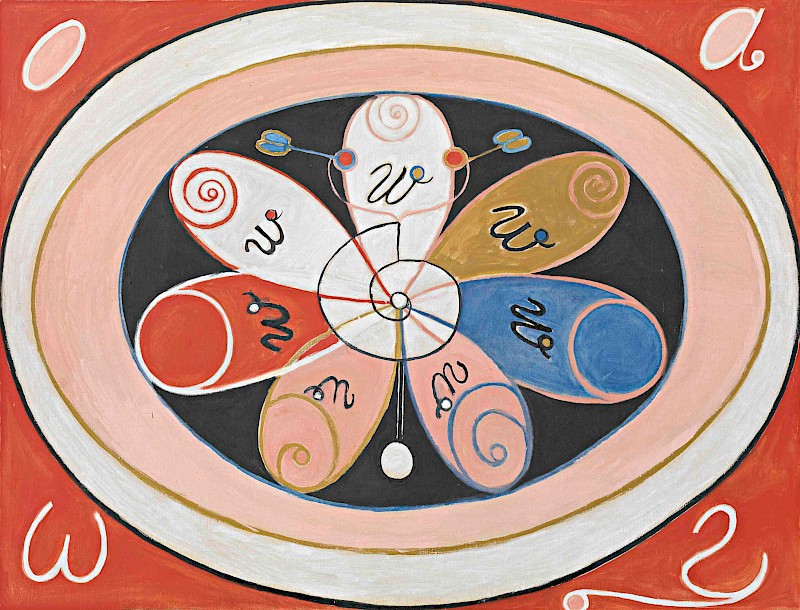

Hilma af Klint – Evolution, No 15, Group IV, The Seven-pointed Stars (1908)

Hilma af Klint’s seminal work “Evolution, No 15” is monumental in scale and worked decisively non-representative in bright, bold colours. She flattened the 2-dimensional space in this world-famous painting in a way that predated other modernist painters by years, initiating the debate about who invented abstract painting.

Traditionally schooled in Fine Arts at the Royal Academy in Sweden, Hilma af Klint rejected her formal training in favour of Spiritualism and worked for many years as a medium. In a major assignment called “Paintings for the Temple” that “Evolution, No 15” is part of, she created a series of works that were to be hung in a spiral temple that would facilitate spiritual meditation and transcendence beyond the physical world.

Even if Klint’s works are nowadays often claimed to be among the first of the abstract paintings, her motivation behind painting was not so much to abstract the depicted objects, but much more to visualize spiritual concepts. Her influential painting “Evolution, 15” can be seen as to be diagramming the immaterial world.

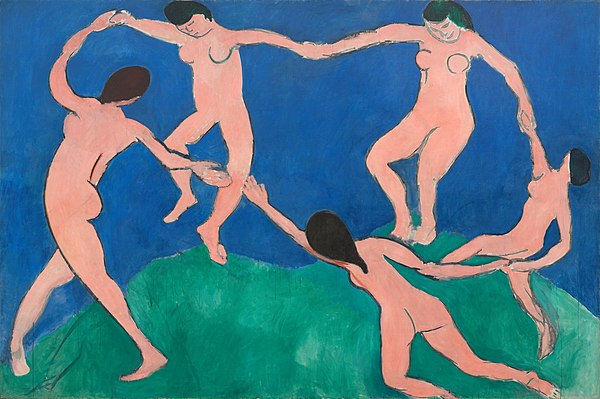

Henri Matisse – The Dance (1909-1910)

Matisse was one of the key leaders of Fauvism, the early 20th-century avant-garde art movement. The Fauvist artists radically reinterpreted the use of colour as a structural and expressive element unrelated to the literal description. The painting shows five figures, painted in red-fleshy colours, dancing in a simplified green landscape with a deep blue background. All figures are drawn loosely and almost completely lack interior definition, while the rhythmical succession of the dancing nudes is reminiscent of hedonism and emotional liberation.

Spatial ambiguity adds to the conflict between the illusion of depth and the acknowledgement of flatness characteristic for the style of Fauvism. When Matisse exhibited his today world-famous painting “The Dance” in the art salons, his aesthetic choices caused a scandal. The bold representation of the nudes, the reduction to primary colours, and the strong colour contrasts made the artwork appear primitive and barbaric in character in the eyes of viewers and art critics.

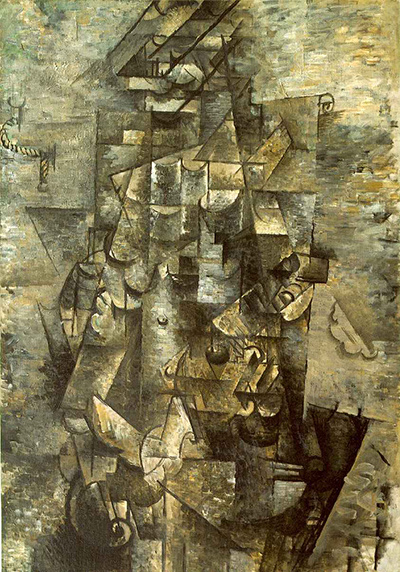

Georges Braque – Man with a Guitar (1911-1912)

Like Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque wanted to challenge the orthodoxy of representative painting of illusionistic space by breaking the subject down into small cubes: The depicted man and his guitar are shown in various sections of geometric shapes such as cones, triangles, cylinders, and spheres, rendering the subject nearly indecipherably. Only at some places are the features recognizable, such as the nail, the rope, and the scroll of the guitar.

Abandoning the traditional use of perspective, Braque created a three-dimensional illusion of space in which the subject is broken down into independent components, often represented from several angles at the same time. The dark palette of browns and blacks in his today world famous painting directs the viewer’s focus completely to these shapes without the distraction of colour. This Analytic Cubism type of abstraction met with a great deal of ridicule and criticism but had a strong impact on other avant-garde artist at the time.

Kazimir Malevich – Black Square (1915)

Most striking about the seminal painting “Black Square” by Kazimir Malewich is that all techniques of traditional painting are omitted. Neither does it utilize standard tonal shading, nor does the artist attempt to use perspective or any description of three-dimensional space. Except for the black square itself, there are no recognizable forms included. Even colour has been rendered in its most binary form: a black square on a white canvas, deliberately representing nothing except for expressing void, the removal of a painterly method.

The Russian artist Malevich had worked in a variety of styles before, seeking inspiration from the Parisian avant-garde including Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque as well as the Italian Futurism. His most important works occurred after 1915 when he primarily concentrated on geometric forms and their relationship with pictorial space. He soon adopted a radical style of non-objective painting, which he called “Suprematism”, which he thought to be a purer form of Cubism – conveying a feeling of undiluted abstraction.

Réne Magritte – The Son of Man (1946)

Belgian painter René Magritte’s dreamlike aesthetic and evocative dreamscapes have ensured him enduring legacy. Strongly influenced by the surrealism art movement, Magritte used visual imagery from the subconscious to create art without the intention of logical comprehensibility. In his world-famous painting “Son of Man”, Magritte plays with the mental conflict of wanting to see and understand what is hidden.

Magritte conceptualized “Son of Man” as a self-portrait. He shows himself as a man wearing a black overcoat and a bowler, standing in front of a low wall frontally facing the viewer. In the more distant background emerges the sea and a grey overcast sky. It is daytime and the sun casts a shadow onto the left side of the man’s face. Unexpectedly, his face is obscured by a hovering plumb green apple with four leaves, hiding the middle part of his face and only leaving his eyes to peek right above the edge of the apple. Further puzzling is the shape of the man’s left arm: The elbow is pointing out as if the man had turned his back towards the viewer.

Like other painters associated with the movement of Surrealism, Magritte sought to overthrow what he considered the oppressive rationalism of the bourgeois society. As in his seminal work “Son of Man”, his art is often filled with discontinuities and frequently disturbing, consistently interrogating conventions of visual representation, casting doubts on the appearance of reality itself.

Jackson Pollock – Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) (1950)

The “Drip painting” technique as applied in the influential painting “Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)” is a form of action painting, characterized by gestural brushstrokes and mark-making, emphasizing the impression of spontaneity. While spontaneity was a central element, the lack of laying out a certain design in advance should not be confused with abandoning control. Pollock stated himself: “I can control the flow of paint: there is no accident.”

Measuring 2.44 high and 5.18 metres wide, “Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)” is one of Jackson Pollock’s largest paintings. Having the canvas lying flat on the ground, Pollock began painting on the one side of the surface, priming it with bundles of black lines, before using devices like sticks, knives, trowels, and cans to build up a dense skein of individually distinguishable lines in different hues and shades of white, gray, black, metallic, teal blue, and brown, using of paint with a fluid viscosity. Afterwards Pollock moved to the centre section and finally to the other side of the painting to repeat the same process of colour application. Pollock thus painted from all four sides of the painting building up a nest-like complexity of interwoven globs and lines. He refrained from defining any focal points or hierarchy of elements – every part of the canvas seems to be equally significant.

Pollock arrived at abstraction after having worked with Mexican muralists. Pollock further studied the philosophy and methods of European Surrealists and had immersed himself in a study of ancient art as well as of Greek mythology. On this basis, he moved back and forth between full abstraction as in “Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)” and figuration. What unites his pictures in any of his artistic periods is that every piece of art had to convey significant and revelatory content.

You might also enjoy reading the following posts by Pigment Pool:

A brief history of colour pigments

Facts to Know about Surrealism: Changing the Course of Art History