“I must see new things and investigate them. I want to taste dark water and see crackling trees and wild winds.”

― Egon Schiele

This article may contain compensated links. Please read Disclaimer for more info. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Introduction to Egon Schiele and Austrian Expressionism

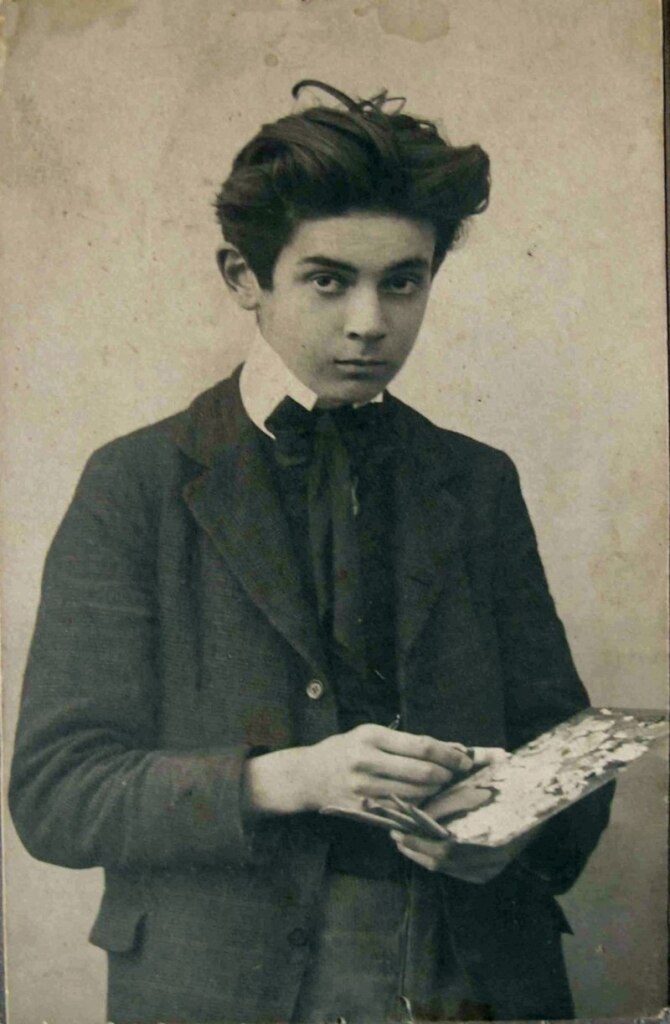

Austrian artist Egon Schiele lived a mere 28 years before succumbing to Spanish influenza in the 1918 pandemic. Since his tragic demise, a cult following has galvanized around the prodigy artist, whose open-minded depiction of the human body was unprecedented in the realm of avant-garde art. In his short life and artistic career, he created a remarkable body of work that vividly communicates profound psychic experiences.

Egon Schiele Facts:

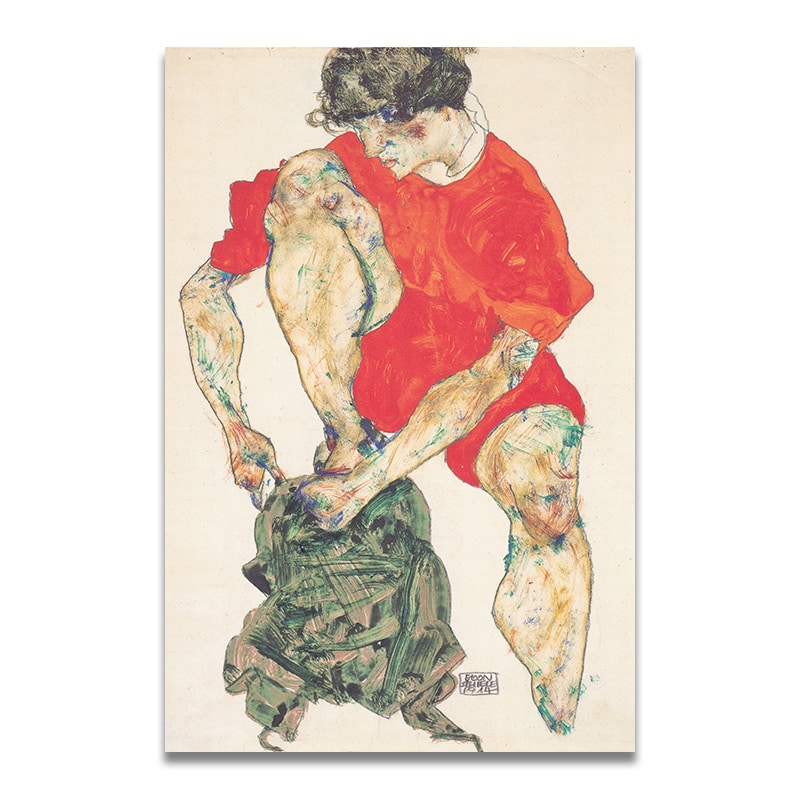

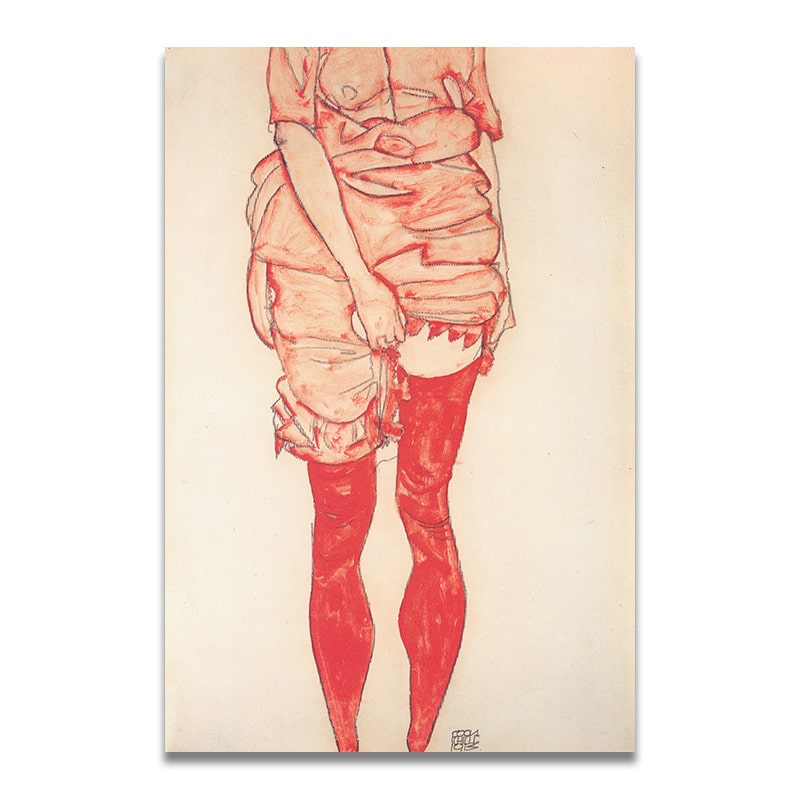

Egon Schiele’s artwork is both known for incorporating the influences of his mentor, Austrian painter Gustav Klimt, and subsequently pioneering the movement of Austrian Expressionism. Like the work of other Austrian Expressionist painters, his outrageous bold and sexual drawings, his many portraits of nude models and himself were highly controversial during his time, were called vulgar and grotesque. Today they are considered masterpieces. Outgrowing his troubled childhood, he led an adventurous and intense life: He practised an extreme lifestyle with models who served as his mistresses, was conscripted to military service during the First World War, and sought to marry a socially acceptable woman. All these incidents had a strong impact on Egon Schiele’s artwork, his career as an artist, and as a proponent of Austrian Expressionism.

Egon Schiele’s upbringing was troubled

The literature describes Egon Schiele’s parents both to be quite complex personalities. And Schiele himself considered his childhood to have been troubled. In 1890 he was born into the decaying Austro-Hungarian Empire as the only son to his parents, Maria and Adolf. His mother had three miscarriages before giving birth to Egon. While one sister died of congenital syphilis at the age of 10, two other sisters survived a normal life span. Schiele had a troubled relationship with his mother and noted in his diaries that he felt misunderstood and unloved.

Egon Schiele’s father was the train station master for the town of Tulln, Lower Austria, and, since he was the only son, it was expected that he would follow the same path and become an engineer. Schiele was fascinated by trains indeed, eagerly drawing them in his sketchbooks. However, the parent’s expectations were dashed due to Schiele’s poor performance in school, where he only excelled in athletics and drawing. Adolf did not recognize the artistic talent and disapproved of his drawing endeavors, frequently burning his son’s sketchbooks full of rage. When Schiele was 11 years old, the family moved to the nearby city of Krems and later to Klosterneuburg for their son to attend secondary school. Schiele was regarded as a strange child among his classmates, shy and reserved. He would usually be in classes with younger classmates.

The father, who frequented brothels in his youth as was usual for well-to-do Austrian men of the time, was first considered mad, and then died from the sexually transmitted disease syphilis when Schiele was 14 years old. The boy became a ward of his maternal uncle, Leopold Czihaczek, who also was a railway official. Leopold likewise expected Schiele to follow in his footsteps, but half-heartedly allowed him a drawing tutor after recognizing the boy’s lack of interest in academia. The father’s death was one of the most far-reaching moments in Schiele’s life. The apparent sexual connotations of the disease and the visible degeneration of Adolf’s health including psychosis would later infuse Egon Schiele’s drawings with associations to sexuality, death, decay, and the inner workings of the human mind.

Schiele’s first female model was his sister

Throughout his career, Schiele focused on the female body as a subject for his artwork. Growing up, he had a close and intense relationship with his four years younger sister Gertrude, Gerti. The siblings were united against their father’s syphilitic tyranny – due to his worsening health condition, the father would often lose his temper and become violent.

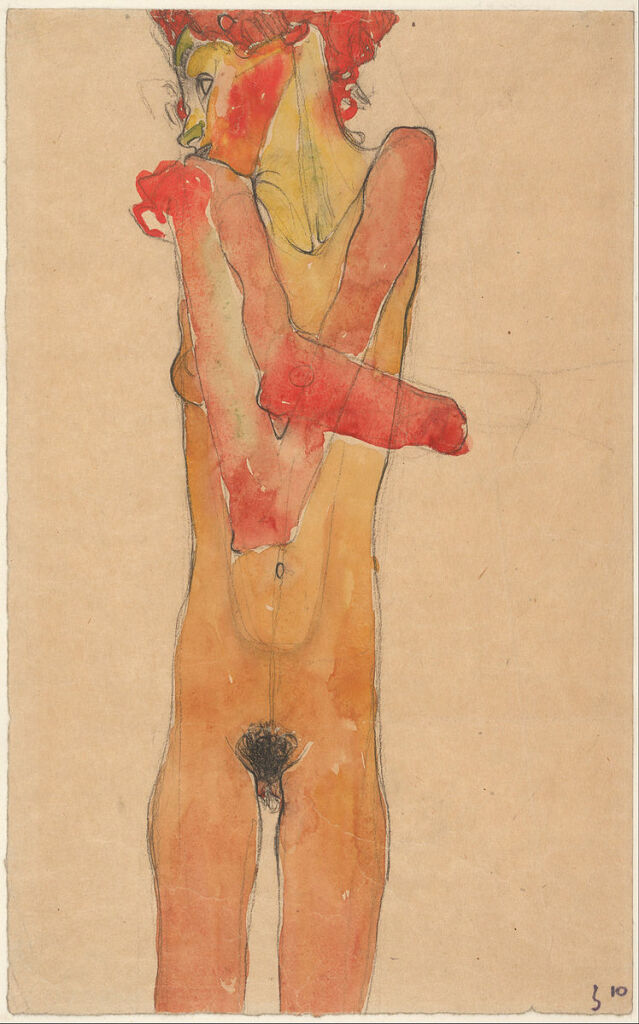

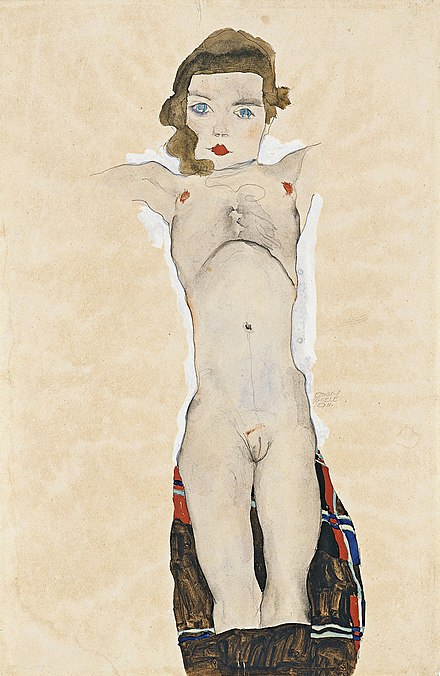

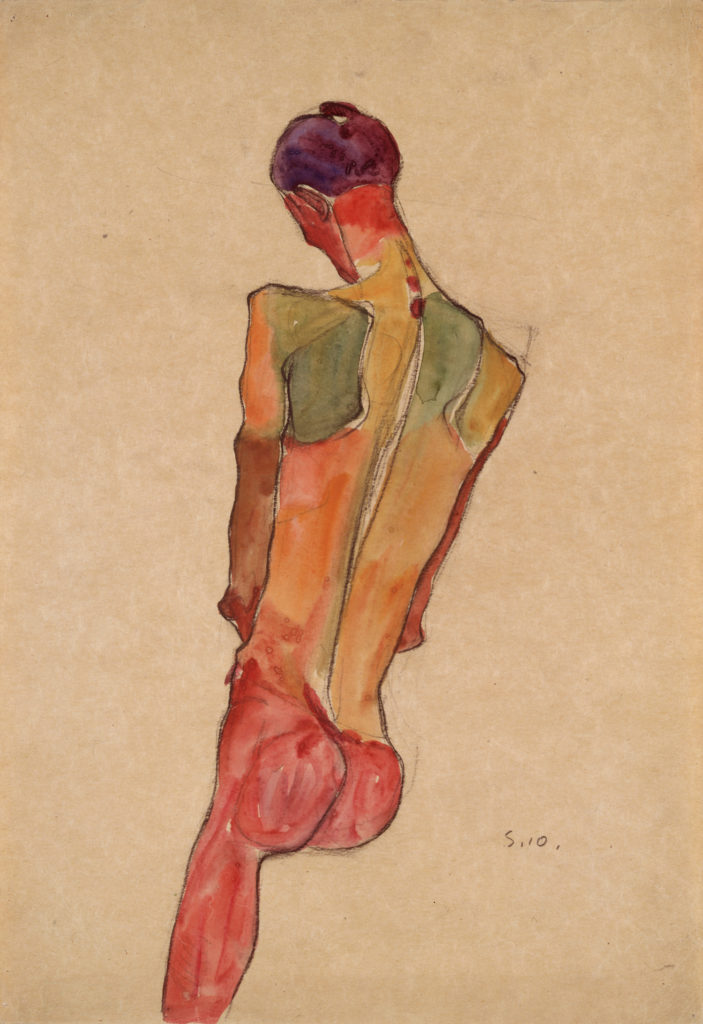

Gerti regularly sat for Schiele as a nude model, and some biographical accounts suggest that their relationship was incestuous. When Schiele was 16 years old, he absconded by train to Trieste with Gerti, where they spent the night together in a hotel room, emulating their parent’s honeymoon. However, while Schiele’s paintings clearly show that he viewed his sister sexually, it is not proven that he acted sexually towards her. She is featured in many of his early works, such as in “Portrait of Gerti Schiele” (1909), as well as in “Nude Girl with Folded Arms (Gertrude Schiele)” (1910), much to their parent’s horror.

Schiele’s first love was doomed

A 2010 book titled “Egon Schiele: The Beginning” tells the story of Schiele’s first teenage love, filling gaps in Egon Schiele’s biography. In the publication, several pages of the boy’s sketchbook surrounding the age of 16 are reproduced. At that time, Egon Schiele’s line drawings already showed a distinct style of intensity and strong expression characteristic for his mature work before he even started formal training. As a love-struck teenager, Schiele drew a girl named Margarete Partonek on the cover of the sketchbook and described her as a “rosy, enchanting creature”.

Only little is known about the girl, beyond her being a teacher’s daughter and a few years younger than Schiele. Six early letters were acquired by the Leopold Museum in Vienna (also called “Schiele Museum”) in 2010, which convey the boy’s love to Margarete and his first attempts at poetry, writing to offer his “right hand to art”, and “both my hands” to “the loveliest girl.” The response of the girl is unknown, however, she kept six love letters and the obituary notice of him, which could be considered signs of mutual affection.

Schiele dropped out of art school

In 1906 Leopold allowed Schiele to apply at the School of Arts and Crafts (Kunstgewerbeschule) in Vienna, where Gustav Klimt had once studied. Within his first year there, the faculty members considered the teaching approach unsuitable for Schiele, who was then sent to the more traditional Academy of Visual Arts (Akademie der Bildenden Künste) in Vienna. Although he was only sixteen years old at that time and the youngest student ever to enrol, Schiele’s talent soon started to get him recognized in the artistic circles of Austria. He was even able to stage his first exhibition in the town of Klostenburg in 1908.

Schiele’s main teacher at the academy was a painter named Christian Griepenkerl, whose ultra-conservative teaching style aggravated and dissatisfied Schiele so much that he decided to leave three years on. Together with other discontented students, including artists Oskar Kokoschka and Max Oppenheimer, he founded the self-styled New Art Group (Neukunstgruppe), for which he wrote the manifesto. Free from academic limitations, Schiele began to explore sexuality and the human form on canvas. After several solo exhibitions, he met art critic Arthur Roessler, who introduced the Austrian painter Schiele to art patrons and well-to-do private collectors.

Student Schiele: Klimt became his mentor

Gustav Klimt facts: While still at the Academy of Visual Arts, Schiele met Gustav Klimt, who was Austria’s foremost artist of the time. Although Klimt had achieved critical success early in his career, with the beginning of the 20th century he sacrificed the field of public commissions to be able to create more provocative, especially erotic works. In Schiele, Klimt recognized a kindred spirit and strongly supported the almost 30 years younger artist’s endeavors. He helped to sell Schiele’s paintings, gave him guidance, introduced him to artists’ circles and to the arts and crafts workshop, the “Wiener Werkstätte”. Elements of Klimt’s avant-garde style can easily be found in numerous of Schiele’s early paintings.

In 1909, Klimt included Schiele’s drawings in the Vienna Art Exhibition (Wiener Kunstschau), where he was exposed to the works of Vincent van Gogh and Edvard Munch. Klimt’s support was decisive for subsequent successes: Schiele further participated in three exhibitions of the New Art Group in Prague (1910), Budapest (1912), and Cologne (1912), as well as in Secessionists shows in Munich and solo shows in the Art Gallery Hans Goltz (1913) and Paris (1914).

While Schiele’s early work was strongly indebted to Klimt in style and choice of topic, he soon developed a distinctive visual language of his own, rejecting the decorative style of Art Nouveau and becoming a major proponent of Expressionism among other Austrian artists of the 20th century. Schiele pictured himself and Klimt in the allegorical work “The Hermits” (1912), in which the younger Schiele apparently engulfs his mentor. Notwithstanding growing apart stylistically, Schiele and Klimt maintained a close personal relationship until both succumbed to the Spanish flu in 1918.

Schiele and Klimt shared a muse

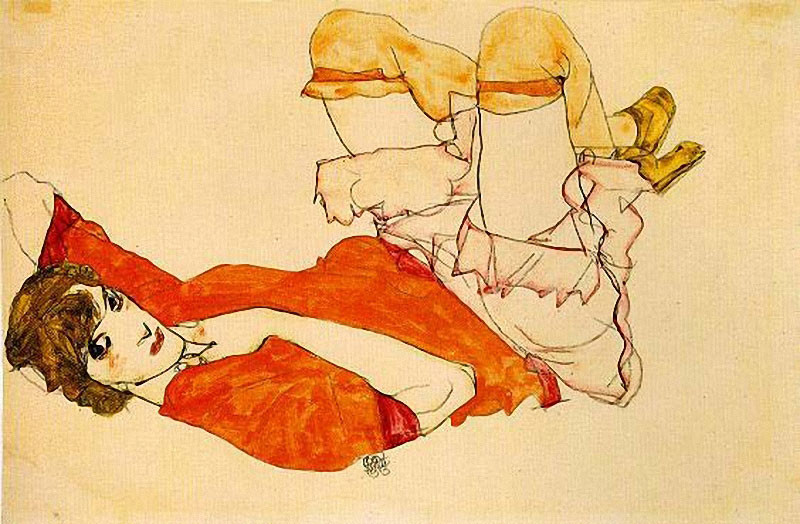

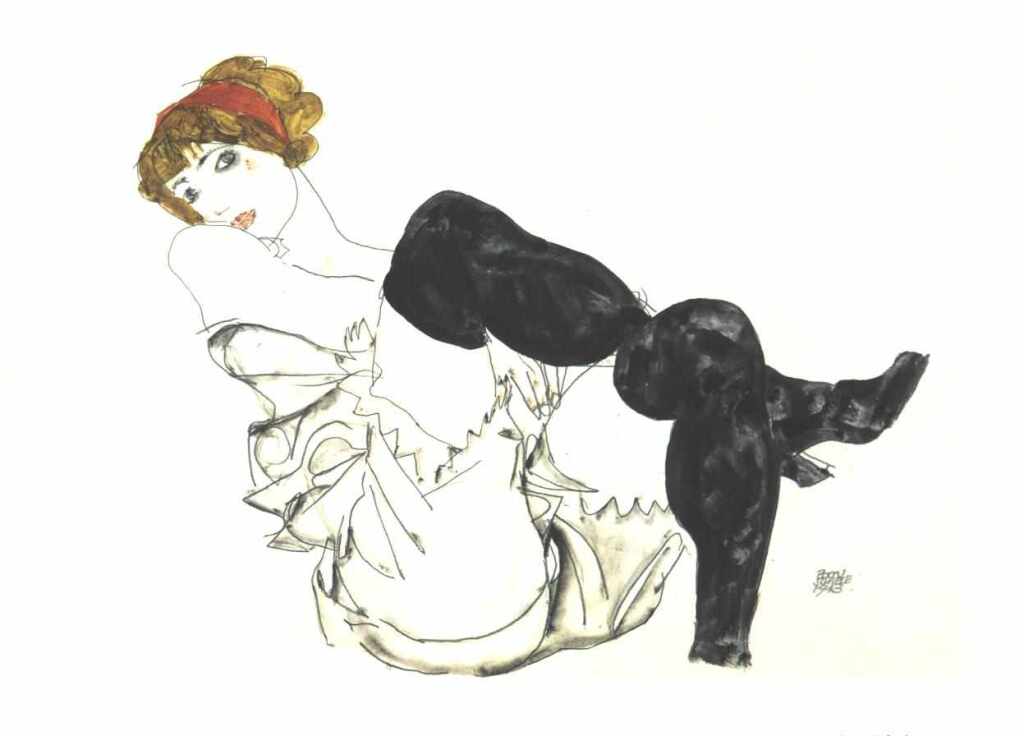

Introduced by Gustav Klimt, Schiele met numerous models who posed for his paintings, including the infamous Walburga (Wally) Neuzil. Wally had previously modelled for Klimt and was most likely his mistress. At the time there was a blurred dividing line between being an artist’s model and being a prostitute, and in the eyes of the bourgeoisie, there was not much difference. Rather often, Klimt, and later Schiele’s models were doubling as prostitutes.

In 1911 Wally, Schiele’s new companion, went to live in Krumau in the Czech Republic with him, which was the beginning of a four-year love affair. While at first, Wally received payment for her modelling work which indicated a certain distance, their artist-model relationship deepened soon. As Schiele indicated in his writings and clearly visible in his art, Wally motivated his self-reflection and became the catalyst for his work.

When Schiele later decided to marry a socially more acceptable woman, Wally’s feelings were strongly hurt and she returned to her former lover, Gustav Klimt – problematic for Schiele as he would note in his diaries. Later, she trained to be a nurse and worked in a war hospital in Vienna during the First World War.

Both Klimt and Schiele were notorious for having love affairs with many different women. Klimt, who never married, is said to have fathered at least 17 children with his models. Schiele often found himself in difficulties with the authorities due to the visitors to his studio, children and women, who would pose nude for him.

Egon Schiele broke away from the Vienna Secession and became a main proponent of Austrian Expressionism

Expressionism Facts: Working in the Art Nouveau style and leading the Vienna Secession, Gustav Klimt was an important forerunner of the Austrian Expressionism movement. His extravagant mode of rendering subjects elaborately patterned, with elongated body parts, and in a bright palette prepared the path for the Expressionists’ use of exotic colours, jagged forms, and sensual lines.

While Egon Schiele emulated the Klimtian approach in his early work, especially looking up to Klimt’s self-portraits, he soon broke away from the style of the Vienna Secession finding his personal approach, seeking to convey raw emotion through provocative images of modern society. Unlike the pastoral scenes of Impressionism or the academic drawings of Neoclassicism, painter Schiele used distorted forms and unnatural pigments to rouse the viewer’s response.

Besides Schiele, Austrian artists like Oskar Kokoschka, Josef Gassler, and Alfred Kubin were inspired by German Expressionism, but never formed an official association. They sought to express the decadence of modern Austrian life with expressive representations of the human body in sinuous lines and distorted figures. Like in Egon Schiele’s art, Kokoschka also imbued his subjects with erotic and psychological themes.

Schiele overstepped the mark of social acceptance

In the beginning of his career, Schiele’s work and his experiments with contorted figures found only little appreciation in Vienna. When he offered some artwork to the design collective Wiener Werkstätte, they were rejected since they lacked the required fluidity deemed necessary for the decorative arts. It took some time until Schiele’s twisted depictions of the human body, and especially his fascination with adolescent girls, came to the surface, shocking and scandalizing contemporary audiences of Austria.

Frustrated by the general response to his work, Schiele sought refuge in his mother’s hometown of Krumau in the Czech Republic, accompanied by his partner Wally. Due to their bawdy lifestyle, the couple immediately raised eyebrows. The youth, on the contrary, flocked to Schiele’s studio, and the artist used the opportunity to draw the adolescent’s bodies that so captivated him. Quickly, gossip spread after sketching a naked girl in the garden of the apartment. The couple was forced to leave the town.

Schiele spent 24 days in prison

Leaving Krumau, the couple moved to Neulengbach, where further scandal followed: A young girl ran away from home, and, knowing of their liberal attitude, sought refuge with Schiele and Wally. She asked the couple to take her to the grandmother in Vienna. Yet once in the city, the girl got cold feet so that the three of them returned to Neulengbach after just one day. By then, the girl’s father had filed charges of abduction and statutory rape. Police came to Schiele’s studio, confiscating 126 works including many nude portraits. During the investigation, a third charge of “public immorality” was leveled against the artists, since he had exposed minors to erotic works of art.

Court records have not been passed down, but it is generally assumed that the charges of abduction and rape were dropped because they could not be verified by the actual occurrences. Yet the third chare of “public immorality” stuck and the artist was sentenced to 24 days in jail, 21 of which he had already served while awaiting the trial.

Schiele was allowed to paint while in prison and sketched out the desolate prison cell in his fluid line, depicting the discomfort of being locked in a cell. On one of his prison drawings, he inscribed: “I do not feel punished, I feel cleansed.” His art changed decisively after his stay in prison, switching from a rebellious unmasking of his subjects’ changing states of being to a more empathic approach. The intensity faded away in favour of a more cautious, cooled-down realism.

Schiele might have been sexually fluid

While for many years it has been thought that Schiele’s pictures of erotically charged female nudes were a representation of raw heterosexuality, recent studies have shown that Schiele might have struggled with sexuality and gender identity. Renowned Schiele scholar Jane Kallir from the Kallir Research Institute believes that underneath the patriarch attitude might have been queerness and sexual fluidity, a questioning of gender norms.

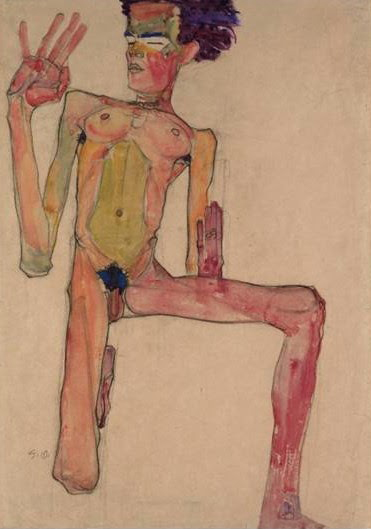

Schiele depicted his models often with androgynous limbs as if transcending gender binaries. On the contrary, he defines himself in his self-portraits explicitly masculine wanting to convey the image of a male genius, for example in pictures with a bawdily large penis. That he deemed this over-emphasis to be necessary has been read as an indication for self-doubt about his own gender identity and generally as self-questioning.

As can be seen in Egon Schiele’s “Two Women” (2015), “Two Hugging Women” (1911) featuring lesbian lovers, homosexuality was no taboo for the artist. Egon Schiele’s lesbian pictures are among his most prominent pictures today. Furthermore, Kallir recently found that Schiele’s male nudes known as “Red Men” were depictions of gay men. Even though the relationship with Wally is well-documented and he later married Edith Harms, records exist that Schiele had a short relationship with a man in 1910 himself.

Since homosexuality was strictly prohibited in Vienna of the early 20th century, it is possible that Schiele intentionally tried to convey a certain image to the world to avoid censorship. It was sufficient that his work was considered erotic and grotesque, pornographic and offensive by the Viennese public.

He married a socially more acceptable woman: Egon Schiele’s wife Edith

Schiele and Wally’s relationship ended abruptly in April 1915. A few months earlier, Schiele had noticed that there were two young girls, Edith and Adele Harms, living across the street from his studio in Vienna at the Hietzinger Hauptstrasse. He started thinking about ways to meet them which was difficult since they lived under the watchful eyes of their parents. Schiele started sending them little notes, some of which have survived. One letter suggests that it was Wally herself who helped introducing Schiele to the two girls and that they went to the cinema together.

Socially more acceptable than Wally with her humble background, he considered marrying one of the two sisters. And since Adele was not interested, he opted for Edith. Despite the strong disapproval of her parents, Edith and Schiele got married on 17th of June 1915, which was the anniversary of the marriage of Schiele’s parents.

In his book “Egon Schiele”, biographer Frank Whitford describes the conflicting emotions, that Edith must have caused in Schiele: “A quiet pleasure in her innocence, a satisfaction with her selfless loyalty mixed with frustration at her lack of sexual energy. Schiele makes her seem passive and whilst he found vulnerability attractive he must also have longed for those quite different qualities which Wally possessed in abundance: the kind of temperament and aggressive eroticism which made Schiele himself feel vulnerable.”

Schiele attempted to cut a deal with Wally asking her to take an annual holiday with him, while Mrs. Edith Schiele was to stay at home. Wally, however, disgusted by his behaviour, refused. Schiele never saw her again.

Schiele had an affair with his sister-in-law

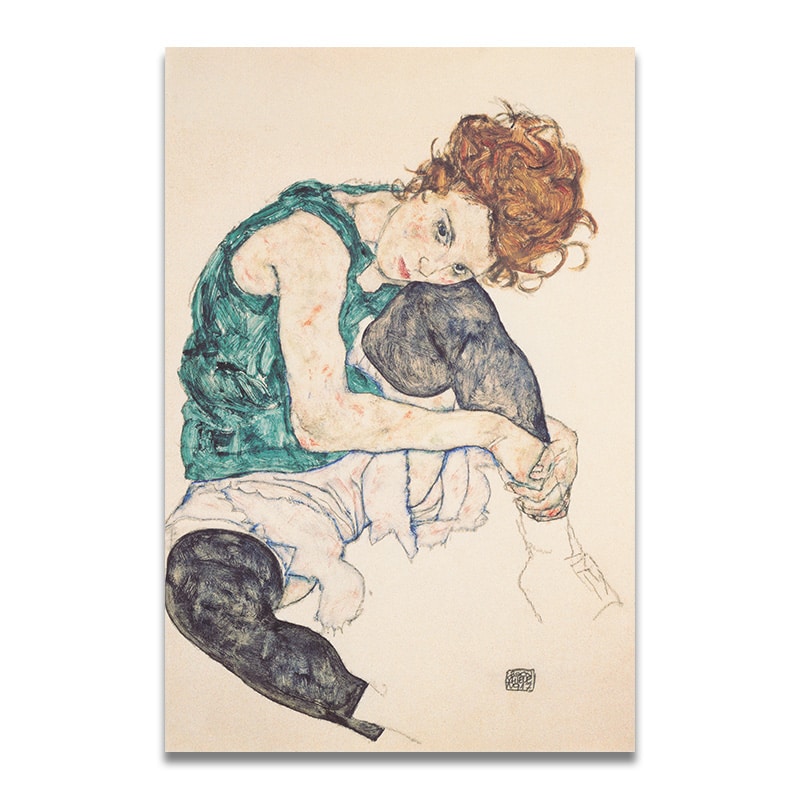

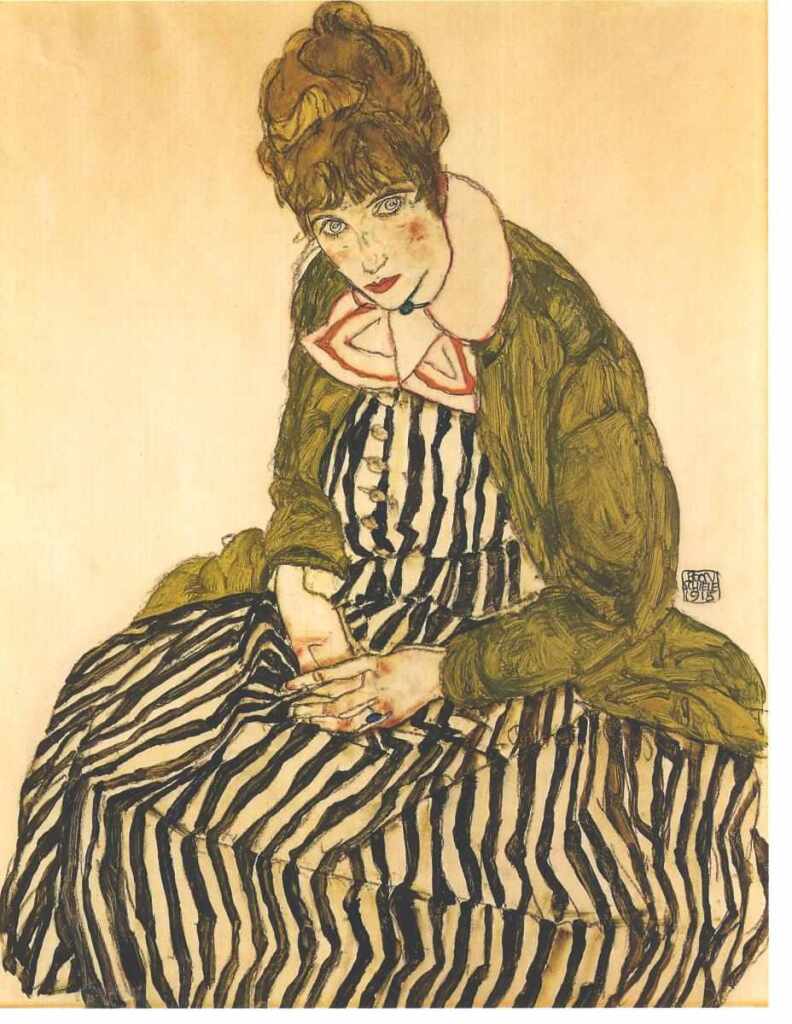

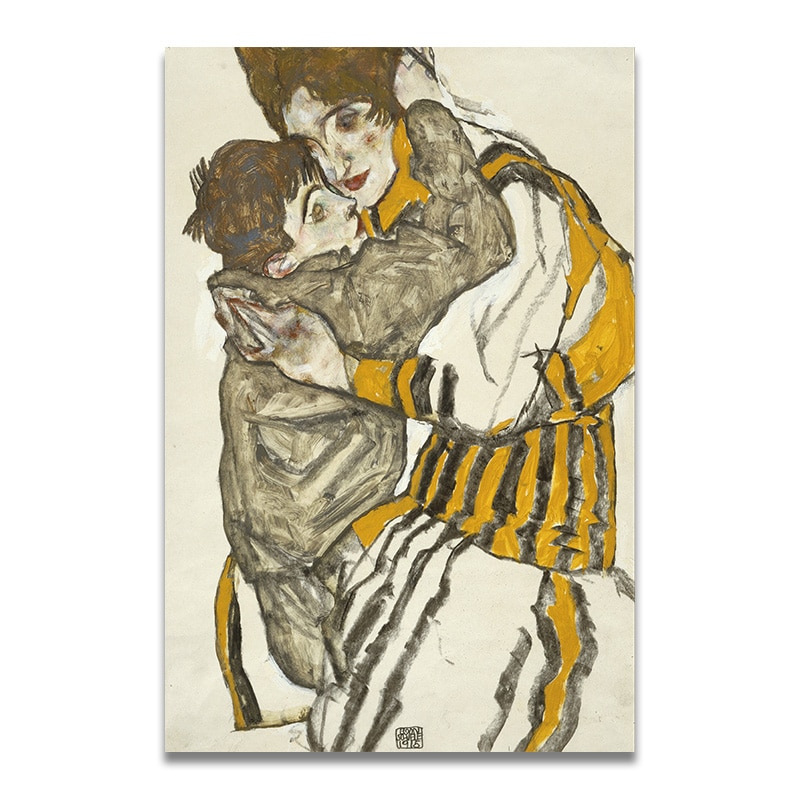

After his marriage, Schiele first concentrated on his wife Edith as a newfound model. He created numerous portraits of her both seated and standing, mostly wearing a striped dress, only occasionally presenting her in erotic poses. During this period, Schiele’s artistic style became more naturalistic, and a certain tenderness appeared. However, the artwork was devoid of the erotic aggressiveness that characterised his earlier pictures of Wally, and later, of his sister-in-law Adele.

Edith’s body changed and she soon put on weight. Not having the slender body that Schiele felt drawn to in painting models anymore, he turned to Adele, who more often would often sit for him. The relationship between the two of them reportedly was not as chaste as it should have been, which also the sexually loaded pictures of Adele indicate.

Schiele painted Russian prisoners of war

Schiele reported for active service in the First World War just three days after his wedding with Edith. His commander Carl Grunwald had been an antique dealer before the war and therefore had a good understanding of art. After seeing some works by the artist, he insisted on buying one of his drawings and provided him with a room Schiele could use as a studio. The commander made every effort to save Schiele to be sent to the front and provided him instead with the task of guarding prisoners of war.

During this period, Schiele started painting on a larger scale and more detailed. Due to a lack of women besides Edith, who stayed in a hotel nearby, most of his sitters were male. While serving as a clerk in a POW camp near the town of Mühling, Schiele’s portraits of imprisoned Russian officers gained widespread acclaim. His military career didn’t prevent him from exhibiting. The artist had successful shows in Berlin, Zürich, Prague, and Dresden. By 1917, he could return to Vienna to focus fully on his artistic career, which lead to prolific output.

Egon Schiele’s self-portraits have been read as signs of narcissism

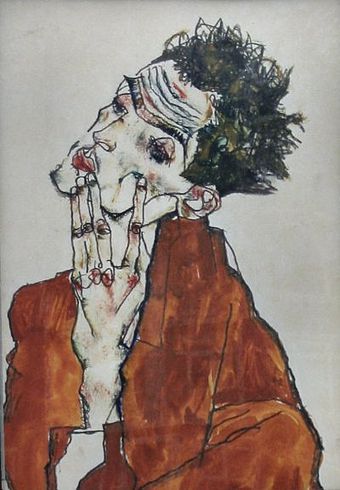

Seeking new means of expression, the Austrian artist Schiele often turned to his own face and body for inspiration. Schiele’s self-portraits are extraordinary not only due to their frequency with which he depicted himself, but even more so for the manner in which he did so: Typically, his self-portraits are brazen in their nudity, with grimacing facial expressions, a contorted body, and knotted limbs. Oftentimes, he would show himself in a mutilated state, castrated, and deformed. Egon Schiele’s self-portrait (1910) “Kneeling Nude with Raised Hands” is considered among the most significant nude art pieces made during the 20th century in this respect.

Reconstructing Schiele’s early life from a psychoanalytical standpoint, some formative events seem to be decisive for his mode of self-representation: A lack of empathy and compassion by his mother, as well as family deaths, including the one of his father from syphilis and those of his four siblings. This is believed to have had an impact on Schiele’s body image and self-representation.

Autoportraits by Schiele as eroticized depictions, in which he often gazes directly at the viewer, suggest confidence in his artistic gifts. Significant are paintings such as his work “The Prophets” (“Double-Self Portrait”), completed in 1911, which is an allegorical portrayal. The “Prophet” who often appears in Christian iconography as an angelic figure, becomes a projection of the artist’s own torment. With a definition as a visionary in his self-portrait, Schiele constructs an image of himself as a mystical clairvoyant.

Schiele had a complex image of family and motherhood

Schiele’s personal biographical background shaped his view of motherhood and family. His father had contracted syphilis before his marriage to his 17-year-old bride but did nothing to treat it. He passed the disease on to his wife, resulting in three miscarriages. A fourth child died at age ten from congenital syphilis when Schiele was four years old. This led to the mother’s ongoing depression, her constant concern about the dangers of syphilis to herself and the surviving children. Most disruptive was how the illness affected his father, his severe psychotic episodes, and finally his death when Schiele was 14 years old.

The father had been a problematic source of male identification to Schiele: His sexuality had made him sick, which again had killed some of his children and disrupted his mental health. Not surprisingly, Schiele found his own sexuality frightening and was worried about his own mental sanity. Having lost his father at the beginning of his puberty, the beginning of his adolescent independence, he was thrown back to sole dependency on his self-centred, disgruntled mother, whom he despised, as many letters indicate.

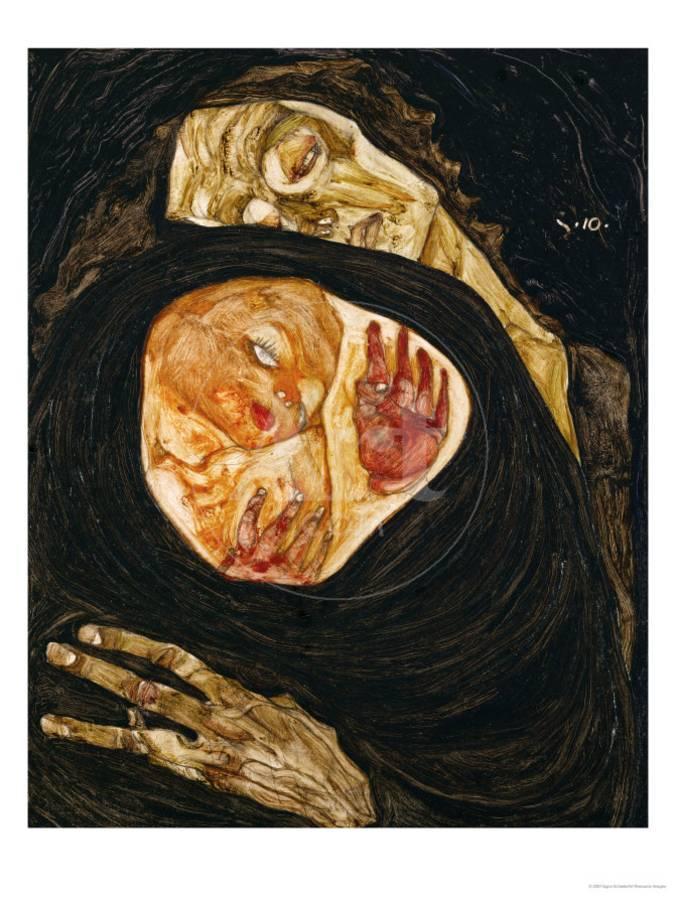

In a series of works showing mothers and children, Schiele portrayed his internal struggle with maternal dependency, his feeling of terrifying dependency on a mother who had given him physical life yet stifled the mental capacities within him. Numerous times, Schiele depicted himself being born to a mother who is blind, dead, or turning her back to him. Pictures such as a charcoal drawing titled “Madonna” show a gloomily dark mother with mesmerising eyes holding an innocent child.

A series of two paintings from the years 1910 and 1911 titled “Dead Mother I and II” depict a baby wrapped in a womb-like blanket as if trapped in the womb of its dead mother, as if afraid about whether it will be able to surface at all. The second painting with the alternate title “Birth of a Genius” show the dead mother, whose fingers have become stiff already. The terrified baby on the other hand has awakened to life. Fear is expressed in his widened stare and his hands, which seem to tear its mother’s womb to be set free.

These images might indicate that Schiele believed he had to fight for his life and that he considered himself to be his own creator. In one letter to his mother, he wrote: “I have only to thank myself for my existence”. His mother on the other hand never forgave him for his uncompromising financial selfishness with which he pursued his career as a painter.

Egon Schiele was influenced by Sigmund Freud

When only 20 years old, Egon Schiele broke radically with the Secessionist movement and simultaneously with the history of figurative painting, focusing on the psychological state of his subjects rather than on their physical characteristics in his paintings. This approach resulted in numberless subversive artworks that unmasked his sitters as emaciated, androgynous, and sexually experimental beings.

While Klimt had explored the erotic aspects of sex, Schiele probed the psychological aspect of eroticism. The latter was not so much interested in the distracting façade of his subjects, but rather in the intriguing psyche that lay underneath. This changing viewpoint was largely due to Sigmund Freud’s book “The Interpretation of Dreams” published in 1900, which many artists had an opinion about.

Most obvious is this influence in Schiele’s shocking nude self-portraits, which he often painted using a full-length standing mirror. In those pictures, he presented himself exhibitionist and at the same time vulnerable, for example in his self-portrait with a huge penis.

Schiele was obsessed with depicting death

The theme of death is omnipresent in the work of Egon Schiele. His preoccupation with images of death is often brought into clear contrast with those of the cycle of life, motherhood, and decay, as seen in the dead mother cycles.

The picture “Death and the Maiden” by Schiele is another allegorical masterpiece that he painted after he married Edith and his request of still being able to go on holidays with Wally was rejected. In the picture, the female figure, Wally, clings grimly to the death figure, Schiele. Her arms seem distended and elastic, unable to retain the fragile grasp on her lover. The swirling lines drag the figures into the centre of a raging vortex, which can be understood as their emotional turbulence. The two characters cling together in despair before being ripped apart forever.

Schiele’s lovers and death theme appears throughout his career. However, in the years after getting married to Edith, both style and mindset undergo significant changes. In “The Embrace”, Schiele depicts a couple lying together, affectionately grasping each other, as if celebrating the union of two people as one harmonious whole.

Schiele died in the Spanish flu pandemic

How did Egon Schiele die?

The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, first observed in Europe, is one of the deadliest in history. It infected around 500 million people worldwide, which was one-third of the world population, killing an estimated 50 million victims. In Austria, the number of deaths from the Spanish Flu rose in 1918 to 18,500 and a further 2,400 died the following year.

Among the many victims of the Spanish Flu in Vienna was artist Egon Schiele: The Austrian Expressionist died at 28. In his last letter to his mother, he described his concern about his pregnant wife, who also died of the flu three days before him. “Dear Mother Schiele, Edith got the Spanish Flu eight days ago and has pneumonia. She is six months pregnant. The disease is very serious and life-threatening; I am preparing myself for the worst.”

In the last days before his death, Schiele drew a few sketches of the dying Edith, which are considered some of the most intimate artworks of Egon Schiele’s wife.

Egon Schiele’s artwork was considered “degenerate art” by the Nazis

The term “degenerate art” (“Entartete Kunst”) was coined in the 1920s by the Nazi Party of Germany to describe avant-garde art of the modern era. Under the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, German and Austrian modern art was removed from state-owned museums, galleries, and collections on the grounds that such artwork was un-German, Jewish, or Communist in nature, or an “insult to German feeling”.

Affected were numerous internationally renowned artists including Egon Schiele, who had many Jewish collectors among his admirers, for instance Fritz Grünbaum, Daisy Hellmann, Josef Morgenstern, and Lea Bondi Jaray. As a result, several restitution cases in the 21st century involved works by Schiele.

The 2012 documentary “Portrait of Wally” tells the dramatic story of Nazi art theft: The picture with the same name as the film title had originally been in the private collection of Lea Bondi Jaray, until looted by the Nazi regime 1939. Rudolf Leopold obtained Schiele’s painting in 1954 for the permanent collection of the Leopold Museum and loaned it to the Museum of Modern Art in New York for an exhibition in 1997. Bondi’s heirs, however, had a subpoena issued while the picture was still in New York, barring the painting’s return to the Leopold collection. After 10 years of litigation, the Leopold Museum agreed to a 19 million USD restitution payment to the heirs.

Multiple art collections are devoted to Schiele’s work

The Schiele Leopold Museum, also called Egon Schiele Museum, Vienna, houses Schiele’s most important and complete collection of work, featuring over 220 works. Besides the Leopold Museum’s Schiele collection, the compendium includes around 6,000 works of Austrian art from the second half of the 19th century and Modernism, among them numerous pieces by Gustav Klimt, Oskar Kokoschka, Alfred Kubin, and Richard Gerstl.

Only a short stroll from the Leopold Museum is the Café Museum in the Operngasse. In this café, Schiele’s Vienna friends such as Gustav Klimt, Oskar Kokoschka, and the Austrian artist himself were regulars.

Another notable collection of Schiele’s art can be seen at the Egon Schiele-Museum in Tulln. The former town prison of Tulln opened on the occasion of Egon Schiele’s 100th birthday in 1990 as the first museum exclusively dedicated to the life and work of Egon Schiele.

The Schiele Museum at the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere in Vienna comprises 20 works, among them 16 paintings. The collection tells the story of these works from their creation to their accession into Belvedere’s collection, shaped by purchases, exchange deals, museum reforms, and restitution.

A further major collection of Schiele’s art is hosted at the Albertina Museum in Vienna, where around 160 significant gouaches and drawings can be seen. A large Egon Schiele exhibition was held in 2017 to set the tone of the commemorative year of 2018.

The Egon Schiele Art Centrum was founded 1993 in Český Krumlov and is also known as Krumau Schiele Museum. In addition to the permanent exhibition of watercolours and drawings, the Egon Schiele Museum in Český Krumlov includes a documentary room devoted to the life and work of the artist, as well as furniture designed by Schiele himself, his death mask, and his only sculpture.

Schiele excelled also in landscape painting

Egon Schiele is best known for his frank representations of the human form. However, besides bluntly revealing portraits and nudes, he also painted outstanding town sceneries and landscapes. Moving to his mother’s hometown of Krumau, modern-day Český Krumlov in the Czech Republic, provoked a creative move within him, turning the artist into a prolific chronicler of the natural and urban environment.

Yet the peaceful backdrop of the pastoral surroundings did not evoke serenity within him but enhanced his preoccupation with isolation and unease, as, for instance, can be seen in Egon Schiele’s autumn trees. Although for Schiele, Krumau was a welcome escape from the decadent alienation in metropolitan Vienna, he transferred his universal themes of mortality, decay, and naked exposure onto the fragmented townscapes.

Like in his portraits, with which he disclosed the twisted turmoil of human anguish, the remote town of Krumau was for Schiele like a visual reflection for his own melancholy, resulting in gloomy pictures like “The Old City”, also known as “The Dead City IV”, showing clustered groups of houses in a nocturnal townscape devoid of habitants. Most of Schiele’s landscape pictures are empty of people, with the sky, rivers, and mountains adding to the oppressive atmosphere.

Schiele continued to paint townscapes of Krumau even after he had returned to Vienna, working from sketches he had made earlier on. One of his most famous landscapes created in 1914 was “Houses with Laundry”, also known as “Two Blocks of Houses with Washing Lines”. This oil on canvas painting is one of the most expensive Schiele artworks sold at auction, according to artnet’s Price Database reaching $39,821,313. The Schiele landscape was sold during Sotheby’s London Impressionist & Modern Art Evening sale in 2011.

Egon Schiele also wrote poetry

Egon Schiele was not only a prolific draughtsman and painter, but also a gifted writer. A collection of his poems and letters authored by Schiele collector Elisabeth Leopold was published in cooperation with the Leopold Museum in 2008. Interspersed with sketches, paintings, and drawings, the artist’s poems and letters, written in his intense and lyrical style, emphasize his emotional struggles, psychological questions, and artistic ambitions.

In April 1918, the year he would succumb to the Spanish flu, Schiele wrote, “…I reckon every artist should be a poet.” “Eternal Child” is the name of one of his most emblematic poems, in which he poetically records the inner fluctuations of his mind.

I, eternal child,

always watched the passage of the rutting people and did not want

to be inside them, I said—spoke and did not speak, I listened and wanted

to hear them and see into them, strongly and more strongly.

Schiele is in popular culture: Egon Schiele tattoos

In recent years, especially since the launch of popular movies about Egon Schiele as well as the 100th anniversary of his death in 2018, the artist has become omnipresent in popular culture. The latest trend is the Egon Schiele tattoo – Schiele fans have some of the most iconic images inked turning their skin into canvas.

Some popular motives are diverse Schiele self-portraits on the shoulder blade, visceral portraits of prostitutes on tummies, or “Mother and Daughter” on the forearm. The latter seems especially appealing due to its balanced composition of the daughter throwing herself into the mother’s arms: the dominant diagonal axis of the girl’s elongated body is balanced by the position of the mother’s face. The scarlet red of the mother’s clothing is contrasted by the light skin of the girl.

Egon Schiele is discussed in the context of the #MeToo movement

Museums staging shows with works by Egon Schiele have been facing issues regarding the fact that his work is largely sexual and widely considered the product of the objectifying male gaze. His own writings suggest that he probably had sexual relationships with underage girls when he himself was in his early 20s. In today’s world and especially since the onset of the #MeToo-movement, this would be called sexual harassment.

Museums deal differently with this problem, either refraining from organizing large Schiele exhibitions or, when staging a show, adding context and caveats in the form of didactic panels describing the character of Egon Schiele. The latter measure was taken by institutions such as the Boston Museum in its big retrospective 2018 on Klimt, Schiele, and other Austrian artists with explanatory panels stating: “Recently, Schiele has been mentioned in the context of sexual misconduct by artists, of the present and the past. This stems in part from specific charges (ultimately dropped as unfounded) of kidnapping and molestation.” Similar measures were taken by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York with its exhibition “Obsession: Nudes by Klimt, Schiele, and Picasso” the same year.

However, Schiele has not been without defenders, who state that circumstances and zeitgeist need to be considered. The Art Newspaper published an article in 2018 with the title “Egon Schiele was not a sex offender” emphasizing the fact that present-day standards differ decisively from those of early 20th century Austria: Because males were not seen as suitable marriage partners until professionally established, they had been expected to consort with prostitutes in their early twenties. Furthermore, the age of consent in fin-de-siècle was 14 in Austria. In this regard, Schiele had been keeping with the norm.

It is hard to tell how “bad” Schiele’s conduct really was based on his own writings and his crimes being recorded in an archaic language. What we do know is that he lived together with 17-year-old Wally, that he liked having teenage girls from modest backgrounds in his studio as models. Schiele’s paintings and drawings include numberless nudes of these models, his sexual obsessions, his voyeurism being explicit throughout his work.

Schiele’s life has inspired novelists and filmmakers

Schiele’s story so rich in passion and tragedies has inspired many novelists and scriptwriters. Especially Schiele’s biography and his relationship with Wally Neuzil have been in the focus of numerous novels and films. For example, Lewis Croft’s “The Pornographer of Vienna” portrays the period of fin-de-siècle Vienna as well as providing in-depth knowledge about the artist himself, packaged in a page-turning novel.

“Arrogance”, a novel by Joanna Scott which won her a nomination for the 1991 PEN/Faulkner Award, tells Schiele’s story from numerous different viewpoints and in many voices. The Austrian artist comes back to life in a narrative that defies, history, identity, and above all, convention.

The German Egon Schiele (2016) Film “Death and the Maiden” by Dieter Berner focuses on the artist’s life as driven by beautiful women and an era that is coming to an end. Besides Schiele, the centre of attention lies in his relationship with his sister Gerti and his true love Wally as immortalized in his famous painting “Death and the Maiden”. Furthermore, an Egon Schiele documentary tells the artist’s story from a different viewpoint. Directed by Teresa Griffiths and first aired on BBC in 2018 on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Schiele’s death, the documentary tells the dramatic story of the artist in his own works, using the artist’s writings and original letters.

You might also be interested in the following posts by Pigment Pool:

Modern and Contemporary Art – What is the Difference?

Impressionism and Japonisme: How Japan Has Inspired Western Artists

The Best Pastels for Artists and Hobbyists in 2022